Undercover No More, Jay Dobyns Revs Up For a Different Fight

The Washington Post

June 21st, 2009

By Neely Tucker, Washington Post Staff Writer

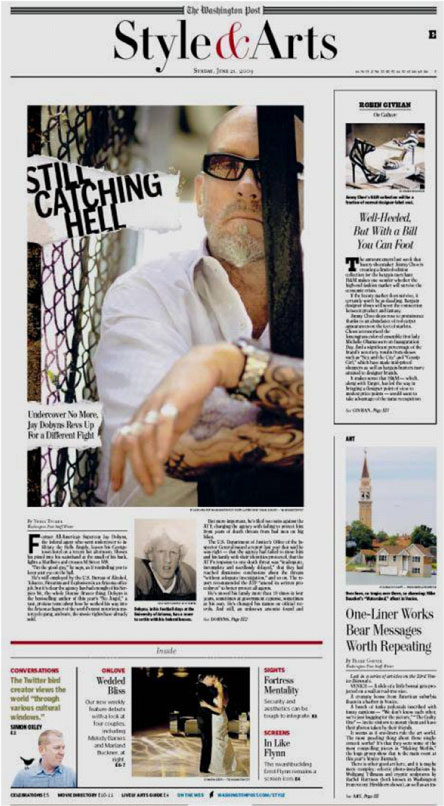

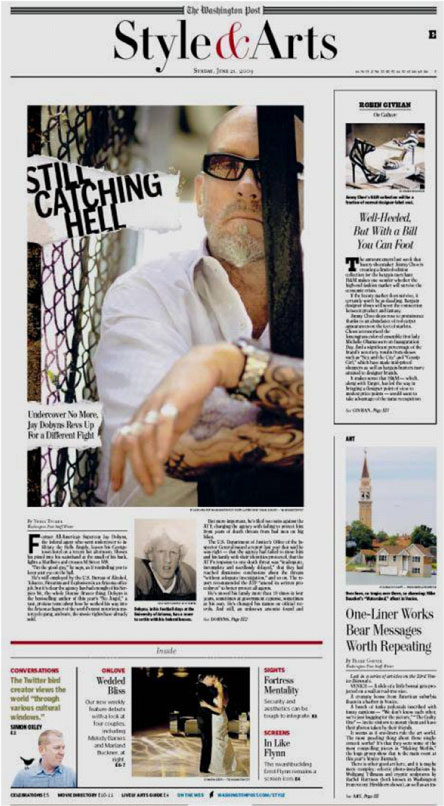

Former All-American Supercop Jay Dobyns, the federal agent who went undercover to infiltrate the Hells Angels, leaves his Georgetown hotel on a recent hot afternoon. Shoves his pistol into his waistband at the small of his back, lights a Marlboro and crosses M Street NW.

"I'm the good guy," he says, as if reminding you to keep your eye on the ball.

He's still employed by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in an Arizona office job, but it's clear the agency has had enough of his Serpico bit, the whole Donnie Brasco thing. Dobyns is the best-selling author of this year's "No Angel," a taut, profane tome about how he worked his way into the Arizona chapter of the world's most notorious motorcycle gang, and sure, the movie rights have already sold.

But more important, he's filed two suits against the ATF, charging the agency with failing to protect him from years of death threats from bad men on big bikes.

The U.S. Department of Justice's Office of the Inspector General issued a report last year that said he was right -- that the agency had failed to move him and his family with their identities protected, that the ATF's response to one death threat was "inadequate, incomplete and needlessly delayed," that they had reached dismissive conclusions about the threats "without adequate investigation," and so on. The report recommended the ATF "amend its written procedures" to better protect all agents.

He's moved his family more than 10 times in four years, sometimes at government expense, sometimes at his own. He's changed his names on official records. And still, an unknown arsonist found and torched his Tucson house one night last August, while he was traveling, sending his wife and two teenage children sprinting into the darkness. An Angel in prison was caught writing a letter to another gang member, saying they should arrange for the gang rape of Dobyns's wife, Gweneth.

"Doesn't sound like a fun evening, does it?" she says, by phone. They've been married 20 years. She sounds great, like Sondra Locke in those Clint Eastwood flicks from the 1970s, a nice girl with good hair who's handy with a pump-action shotgun.

Here comes her husband now, stepping into an Italian restaurant: Shaved head, goatee, shades, jeans, embroidered white silk shirt (untucked), flip-flops, baseball cap, biceps, blue eyes, 47. About 6-1, 220, former honorable-mention all-Pac-10 wide receiver at the University of Arizona. He is "fully sleeved," as they say in the world of skin ink, tattoos covering both arms, shoulder to wrist. Silver rings on almost every finger. Espresso addict, chain smoker. He's stopped doing handfuls of Hydroxycut, the diet pills, the legal uppers, that kept him stoked when he was riding with the Angels, hands thrown up on the ape hangers, but he still looks like if he hit you, you'd stay hit.

"I'm not anybody's knight in shining armor," he's saying, explaining why he's committing career suicide, filing suits like this, alerting members of Congress of his claims, "but there's a greater good here. Nobody has ever stood up to these guys before."

He digs into the pasta and flips through the shorthand notes he penned in all capital letters, in red ink, for today's interview: "Only people who hate me more than the Hells Angels are ATF's shot-callers." And: "I have God and a gun on my side -- I will be OK." And: "U.S. gov't left me alone to defend my family from an international crime syndicate."

He's no longer in hiding; he's full-bore into the lawsuits. He'll go on for two minutes or two hours, it's up to you, about how the ATF accused him of burning his own house down and said he was "mentally unfit" to work. He says a recent mediation hearing produced this offer from the agency: Quit or be fired.

One suit was filed last October in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims in D.C.; the ATF is contesting the venue. The other suit, filed in federal court in Arizona in March, is not yet due for a response from the agency. A spokesman declined to comment on Dobyns's allegations. More on that in a minute.

First, let's go back to the beginning. The Hells Angels case was supposed to be a career capper.

Dobyns, an undercover agent with ATF for 15 years, was a highly regarded pro working a case in Bullhead City, Ariz., in 2001, with the covert identity of Jay "Bird" Davis. He was posing as a gun-runner and collections-agent thug for the fictional business Imperial Financial.

He was in mid-investigation in April 2002 when the Angels and the Mongols, another rough-hewn cycle gang, fell into a riot at Harrah's casino in Laughlin, Nev. Two Angels and one Mongol were killed and dozens injured. The ATF decided to go after the 2,500-member Angels, with the theory that the gang constituted a racketeering organization.

To do this, Dobyns and another agent put together a "gang," composed of two other undercover agents and two paid informants. The lead informant, Rudy Kramer, was a longtime biker and meth dealer, and an inactive member of a Tijuana-based cycle gang called the Solo Angeles. Their gang had Kramer as president, Dobyns as vice president. They would tool around Arizona, profess their love and admiration for the Hells Angels and ask for permission to set up a formal nomad chapter of the Solo Angeles in their area. From there, they'd try to worm their way into the Angels' good graces and alleged criminal doings, thereby laying the groundwork for a massive conspiracy indictment.

Dobyns's group worked for nearly two years. They rode thousands of miles with the Angels. He learned things; he could wave off drinks by always having a smoke in hand. "I sacrificed my lungs to save my liver." He could pass on hits of cocaine, weed and meth by saying that he worked for a Mafia boss who kept him on call every hour of every day. He enlisted a female agent to pose as his girlfriend, to give him a plausible excuse to pass on the offers of sex from female hangers-on.

He went so deeply into being Bird that he says he became "obsessed," all but forgetting his wife and children. It took a toll on his marriage. He got a lot of tattoos, mainly from an Angel named Robert "Mac" McKay, and hammered down caffeine, Red Bulls and diet pills to get that eyes-glazed gonzo look.

He and a colleague staged an execution of a Mongol (actually, another cop) to impress the Angels brass. They dressed the cop in Mongols gear, tied his hands behind his back, put him face down in the desert, then mussed cow brains through his hair and spattered his clothes with blood. They took a happy snap of the gore and brought back the bloody Mongol vest. That earned Dobyns an invitation to join the club, and then the net swooped in for the arrests.

"I felt like Lewis and Clark when they laid eyes on the Pacific, or Neil Armstrong when his boot hit moon dirt," he writes in the book.

Not afraid of publicity, he went on cable television documentaries, even wearing a cowboy hat in one, describing his exploits. Two true-crime books were written about the investigation before his own memoir. He set up a slick Web site, showcasing his college football heroics, his bad-ass biker persona (scowl, bandanna, tats, bulging biceps, the obligatory wife-beater) and his motivational speaking gigs.

This is all great . . . except for the unhappy fact that the case collapsed before trial. No Angel did time for anything much more serious than being in possession of a firearm. Most of them walked. Dobyns says it was due to infighting between ATF higher-ups and the local prosecutor's office.

Then came the threats. He and his family went on the run, his suit maintains, and the ATF mishandled the moves, delayed investigating the threats and came to regard him as a showboating pain in the rear.

"In nearly every respect, [the Angels] won," he writes in the book. Let's talk to some Hells Angels. Let's see what they make of Jay Dobyns. Let's start at the top, the godfather of the band, Sonny Barger.

We've got his attorney Fritz Clapp on the line, and we're explaining about Dobyns and death threats and we'd like to see what Mr. Barg -- "We're not giving him any publicity to sell his book," Clapp interrupts, amicably. "No comment."

Fine. We ask for his official title with the Angels, and Clapp says, "I'm the guy who says, 'No comment.' " He went on to trade bike stories, about this time he was injured and several bikers were killed in a collision with a runaway pulpwood truck -- "It was raining logs" -- but we digress.

Let's talk to an Angel who allegedly threatened to kill Dobyns.

"The man's a sociopath." This is Robert "Mac" McKay on the line -- an Angel calling a cop a sociopath, what are the odds -- from his tattoo shop, the Black Rose, in Tucson. McKay spent 17 months in jail awaiting trial on a variety of charges after Dobyns's investigation. He eventually took a plea to a single misdemeanor for threatening Dobyns in a bar.

"The whole investigation thing, the government spent millions of dollars on what turned out to be a publicity stunt for Jay Dobyns," McKay says. He adds that the alleged threat was "a total fabrication."

So, do the Angels want Dobyns dead? Did they cause his house to burn down?

"Absolutely not. He is not under any threat from us and never has been. He's got this thing in his mind about who he is. . . . Even the ATF says he's useless."

McKay's court-appointed lawyer, Barbara Hull, says, "The whole case went south quickly, and it was pretty clear it had to do with Agent Dobyns."

The assistant U.S. attorney who prosecuted the case, Tim Duax, now based in Iowa, says that's nonsense.

"Jay's undercover work was solid," Duax says. The allegation that he did something unethical that deep-sixed the case? "Absolutely untrue." The reason the case disintegrated? "Had nothing to do with Agent Dobyns."

So how did it come to this, sitting in a restaurant, giving a postmortem on his career? Dobyns says it's simple: The threats came in, were mishandled, he complained in high-octane fashion and alienated people high up in the organization. His suit is filled with allegations that superiors have told him he'll be ending his career in "a postage stamp in the middle of nowhere," that they think he burned down his own house.

"They took three days to send anybody out to look at the house," he says. "And when I complained about their offered solution -- to move us again -- within two hours they told me I was the chief suspect."

This does not strike some veteran agents as unusual. William "Billy" Queen is a legendary ATF agent who infiltrated the Mongols in California several years ago, netting dozens of felony convictions for serious crimes. His reward, he says, was that "the ATF ruined my life."

He says that when the agency moved him out of the area to protect him from death threats, he was needlessly split from his ex-wife and children (who lived nearby, and wanted to relocate with him). They were shipped to Miami. He was shipped to Plano, Tex. He cites a personal vendetta from a high-ranking (now retired) ATF administrator as the cause. It was so bad, Queen says, that he retired.

"What they did to me was worse than what they've done to Jay," he says, in a telephone interview from his home in California. He never sued but "looking back on it now, I wish I would have."

Charlie Fuller, the executive director of the International Association of Undercover Officers, spent 23 years with the ATF. He trained undercover agents for the agency for years, including Dobyns. He says that while he loves his former employer, it has an "institutional suspicion" of its undercover agents.

"ATF considers undercovers a necessary evil," Fuller says. "They don't fit the mold. They don't look like the chief of police. Jay didn't do dope, didn't cheat, didn't beat people up. That's actually hard to do, in those operations, with those type of people, but ATF can't believe that. They can't believe you work guys like that and not do all that stuff. That's what they visualize."

Still, he says, when he heard the agency was saying that Dobyns set fire to his own house, "it sent me over the edge. I can't tell you how this is eating at me."

The ATF was asked about these and other statements. Here is the response:

"ATF is aware of the recent publication of Mr. Dobyns' book. The book is not an ATF publication, and as such, ATF will not comment on its content. Further, ATF does not, as a matter of policy, comment on personnel matters or pending litigation." It's attributed to W. Larry Ford, the assistant director for public and governmental affairs.

Jay Dobyns finishes his lunch and heads back out into the sunshine. He's got another meeting, something to do with the lawsuit, before catching a flight back home. Shades and baseball cap back on. He's hurrying. He's got a sense of purpose. He's not happy. Blue-eyed crime fighters with prominent jaws aren't supposed to end up like this.

Watching him go, you wonder how it's all going to end, the jilted agent now fighting his own agency, and it doesn't look good for anybody. Maybe he was right. Maybe the Angels, still riding, still the most powerful motorcycle gang on the planet, really did run over him.

Former All-American Supercop Jay Dobyns, the federal agent who went undercover to infiltrate the Hells Angels, leaves his Georgetown hotel on a recent hot afternoon. Shoves his pistol into his waistband at the small of his back, lights a Marlboro and crosses M Street NW.

"I'm the good guy," he says, as if reminding you to keep your eye on the ball.

He's still employed by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in an Arizona office job, but it's clear the agency has had enough of his Serpico bit, the whole Donnie Brasco thing. Dobyns is the best-selling author of this year's "No Angel," a taut, profane tome about how he worked his way into the Arizona chapter of the world's most notorious motorcycle gang, and sure, the movie rights have already sold.

But more important, he's filed two suits against the ATF, charging the agency with failing to protect him from years of death threats from bad men on big bikes.

The U.S. Department of Justice's Office of the Inspector General issued a report last year that said he was right -- that the agency had failed to move him and his family with their identities protected, that the ATF's response to one death threat was "inadequate, incomplete and needlessly delayed," that they had reached dismissive conclusions about the threats "without adequate investigation," and so on. The report recommended the ATF "amend its written procedures" to better protect all agents.

He's moved his family more than 10 times in four years, sometimes at government expense, sometimes at his own. He's changed his names on official records. And still, an unknown arsonist found and torched his Tucson house one night last August, while he was traveling, sending his wife and two teenage children sprinting into the darkness. An Angel in prison was caught writing a letter to another gang member, saying they should arrange for the gang rape of Dobyns's wife, Gweneth.

"Doesn't sound like a fun evening, does it?" she says, by phone. They've been married 20 years. She sounds great, like Sondra Locke in those Clint Eastwood flicks from the 1970s, a nice girl with good hair who's handy with a pump-action shotgun.

Here comes her husband now, stepping into an Italian restaurant: Shaved head, goatee, shades, jeans, embroidered white silk shirt (untucked), flip-flops, baseball cap, biceps, blue eyes, 47. About 6-1, 220, former honorable-mention all-Pac-10 wide receiver at the University of Arizona. He is "fully sleeved," as they say in the world of skin ink, tattoos covering both arms, shoulder to wrist. Silver rings on almost every finger. Espresso addict, chain smoker. He's stopped doing handfuls of Hydroxycut, the diet pills, the legal uppers, that kept him stoked when he was riding with the Angels, hands thrown up on the ape hangers, but he still looks like if he hit you, you'd stay hit.

"I'm not anybody's knight in shining armor," he's saying, explaining why he's committing career suicide, filing suits like this, alerting members of Congress of his claims, "but there's a greater good here. Nobody has ever stood up to these guys before."

He digs into the pasta and flips through the shorthand notes he penned in all capital letters, in red ink, for today's interview: "Only people who hate me more than the Hells Angels are ATF's shot-callers." And: "I have God and a gun on my side -- I will be OK." And: "U.S. gov't left me alone to defend my family from an international crime syndicate."

He's no longer in hiding; he's full-bore into the lawsuits. He'll go on for two minutes or two hours, it's up to you, about how the ATF accused him of burning his own house down and said he was "mentally unfit" to work. He says a recent mediation hearing produced this offer from the agency: Quit or be fired.

One suit was filed last October in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims in D.C.; the ATF is contesting the venue. The other suit, filed in federal court in Arizona in March, is not yet due for a response from the agency. A spokesman declined to comment on Dobyns's allegations. More on that in a minute.

First, let's go back to the beginning. The Hells Angels case was supposed to be a career capper.

Dobyns, an undercover agent with ATF for 15 years, was a highly regarded pro working a case in Bullhead City, Ariz., in 2001, with the covert identity of Jay "Bird" Davis. He was posing as a gun-runner and collections-agent thug for the fictional business Imperial Financial.

He was in mid-investigation in April 2002 when the Angels and the Mongols, another rough-hewn cycle gang, fell into a riot at Harrah's casino in Laughlin, Nev. Two Angels and one Mongol were killed and dozens injured. The ATF decided to go after the 2,500-member Angels, with the theory that the gang constituted a racketeering organization.

To do this, Dobyns and another agent put together a "gang," composed of two other undercover agents and two paid informants. The lead informant, Rudy Kramer, was a longtime biker and meth dealer, and an inactive member of a Tijuana-based cycle gang called the Solo Angeles. Their gang had Kramer as president, Dobyns as vice president. They would tool around Arizona, profess their love and admiration for the Hells Angels and ask for permission to set up a formal nomad chapter of the Solo Angeles in their area. From there, they'd try to worm their way into the Angels' good graces and alleged criminal doings, thereby laying the groundwork for a massive conspiracy indictment.

Dobyns's group worked for nearly two years. They rode thousands of miles with the Angels. He learned things; he could wave off drinks by always having a smoke in hand. "I sacrificed my lungs to save my liver." He could pass on hits of cocaine, weed and meth by saying that he worked for a Mafia boss who kept him on call every hour of every day. He enlisted a female agent to pose as his girlfriend, to give him a plausible excuse to pass on the offers of sex from female hangers-on.

He went so deeply into being Bird that he says he became "obsessed," all but forgetting his wife and children. It took a toll on his marriage. He got a lot of tattoos, mainly from an Angel named Robert "Mac" McKay, and hammered down caffeine, Red Bulls and diet pills to get that eyes-glazed gonzo look.

He and a colleague staged an execution of a Mongol (actually, another cop) to impress the Angels brass. They dressed the cop in Mongols gear, tied his hands behind his back, put him face down in the desert, then mussed cow brains through his hair and spattered his clothes with blood. They took a happy snap of the gore and brought back the bloody Mongol vest. That earned Dobyns an invitation to join the club, and then the net swooped in for the arrests.

"I felt like Lewis and Clark when they laid eyes on the Pacific, or Neil Armstrong when his boot hit moon dirt," he writes in the book.

Not afraid of publicity, he went on cable television documentaries, even wearing a cowboy hat in one, describing his exploits. Two true-crime books were written about the investigation before his own memoir. He set up a slick Web site, showcasing his college football heroics, his bad-ass biker persona (scowl, bandanna, tats, bulging biceps, the obligatory wife-beater) and his motivational speaking gigs.

This is all great . . . except for the unhappy fact that the case collapsed before trial. No Angel did time for anything much more serious than being in possession of a firearm. Most of them walked. Dobyns says it was due to infighting between ATF higher-ups and the local prosecutor's office.

Then came the threats. He and his family went on the run, his suit maintains, and the ATF mishandled the moves, delayed investigating the threats and came to regard him as a showboating pain in the rear.

"In nearly every respect, [the Angels] won," he writes in the book. Let's talk to some Hells Angels. Let's see what they make of Jay Dobyns. Let's start at the top, the godfather of the band, Sonny Barger.

We've got his attorney Fritz Clapp on the line, and we're explaining about Dobyns and death threats and we'd like to see what Mr. Barg -- "We're not giving him any publicity to sell his book," Clapp interrupts, amicably. "No comment."

Fine. We ask for his official title with the Angels, and Clapp says, "I'm the guy who says, 'No comment.' " He went on to trade bike stories, about this time he was injured and several bikers were killed in a collision with a runaway pulpwood truck -- "It was raining logs" -- but we digress.

Let's talk to an Angel who allegedly threatened to kill Dobyns.

"The man's a sociopath." This is Robert "Mac" McKay on the line -- an Angel calling a cop a sociopath, what are the odds -- from his tattoo shop, the Black Rose, in Tucson. McKay spent 17 months in jail awaiting trial on a variety of charges after Dobyns's investigation. He eventually took a plea to a single misdemeanor for threatening Dobyns in a bar.

"The whole investigation thing, the government spent millions of dollars on what turned out to be a publicity stunt for Jay Dobyns," McKay says. He adds that the alleged threat was "a total fabrication."

So, do the Angels want Dobyns dead? Did they cause his house to burn down?

"Absolutely not. He is not under any threat from us and never has been. He's got this thing in his mind about who he is. . . . Even the ATF says he's useless."

McKay's court-appointed lawyer, Barbara Hull, says, "The whole case went south quickly, and it was pretty clear it had to do with Agent Dobyns."

The assistant U.S. attorney who prosecuted the case, Tim Duax, now based in Iowa, says that's nonsense.

"Jay's undercover work was solid," Duax says. The allegation that he did something unethical that deep-sixed the case? "Absolutely untrue." The reason the case disintegrated? "Had nothing to do with Agent Dobyns."

So how did it come to this, sitting in a restaurant, giving a postmortem on his career? Dobyns says it's simple: The threats came in, were mishandled, he complained in high-octane fashion and alienated people high up in the organization. His suit is filled with allegations that superiors have told him he'll be ending his career in "a postage stamp in the middle of nowhere," that they think he burned down his own house.

"They took three days to send anybody out to look at the house," he says. "And when I complained about their offered solution -- to move us again -- within two hours they told me I was the chief suspect."

This does not strike some veteran agents as unusual. William "Billy" Queen is a legendary ATF agent who infiltrated the Mongols in California several years ago, netting dozens of felony convictions for serious crimes. His reward, he says, was that "the ATF ruined my life."

He says that when the agency moved him out of the area to protect him from death threats, he was needlessly split from his ex-wife and children (who lived nearby, and wanted to relocate with him). They were shipped to Miami. He was shipped to Plano, Tex. He cites a personal vendetta from a high-ranking (now retired) ATF administrator as the cause. It was so bad, Queen says, that he retired.

"What they did to me was worse than what they've done to Jay," he says, in a telephone interview from his home in California. He never sued but "looking back on it now, I wish I would have."

Charlie Fuller, the executive director of the International Association of Undercover Officers, spent 23 years with the ATF. He trained undercover agents for the agency for years, including Dobyns. He says that while he loves his former employer, it has an "institutional suspicion" of its undercover agents.

"ATF considers undercovers a necessary evil," Fuller says. "They don't fit the mold. They don't look like the chief of police. Jay didn't do dope, didn't cheat, didn't beat people up. That's actually hard to do, in those operations, with those type of people, but ATF can't believe that. They can't believe you work guys like that and not do all that stuff. That's what they visualize."

Still, he says, when he heard the agency was saying that Dobyns set fire to his own house, "it sent me over the edge. I can't tell you how this is eating at me."

The ATF was asked about these and other statements. Here is the response:

"ATF is aware of the recent publication of Mr. Dobyns' book. The book is not an ATF publication, and as such, ATF will not comment on its content. Further, ATF does not, as a matter of policy, comment on personnel matters or pending litigation." It's attributed to W. Larry Ford, the assistant director for public and governmental affairs.

Jay Dobyns finishes his lunch and heads back out into the sunshine. He's got another meeting, something to do with the lawsuit, before catching a flight back home. Shades and baseball cap back on. He's hurrying. He's got a sense of purpose. He's not happy. Blue-eyed crime fighters with prominent jaws aren't supposed to end up like this.

Watching him go, you wonder how it's all going to end, the jilted agent now fighting his own agency, and it doesn't look good for anybody. Maybe he was right. Maybe the Angels, still riding, still the most powerful motorcycle gang on the planet, really did run over him.

Former All-American Supercop Jay Dobyns, the federal agent who went undercover to infiltrate the Hells Angels, leaves his Georgetown hotel on a recent hot afternoon. Shoves his pistol into his waistband at the small of his back, lights a Marlboro and crosses M Street NW.

"I'm the good guy," he says, as if reminding you to keep your eye on the ball.

He's still employed by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in an Arizona office job, but it's clear the agency has had enough of his Serpico bit, the whole Donnie Brasco thing. Dobyns is the best-selling author of this year's "No Angel," a taut, profane tome about how he worked his way into the Arizona chapter of the world's most notorious motorcycle gang, and sure, the movie rights have already sold.

But more important, he's filed two suits against the ATF, charging the agency with failing to protect him from years of death threats from bad men on big bikes.

The U.S. Department of Justice's Office of the Inspector General issued a report last year that said he was right -- that the agency had failed to move him and his family with their identities protected, that the ATF's response to one death threat was "inadequate, incomplete and needlessly delayed," that they had reached dismissive conclusions about the threats "without adequate investigation," and so on. The report recommended the ATF "amend its written procedures" to better protect all agents.

He's moved his family more than 10 times in four years, sometimes at government expense, sometimes at his own. He's changed his names on official records. And still, an unknown arsonist found and torched his Tucson house one night last August, while he was traveling, sending his wife and two teenage children sprinting into the darkness. An Angel in prison was caught writing a letter to another gang member, saying they should arrange for the gang rape of Dobyns's wife, Gweneth.

"Doesn't sound like a fun evening, does it?" she says, by phone. They've been married 20 years. She sounds great, like Sondra Locke in those Clint Eastwood flicks from the 1970s, a nice girl with good hair who's handy with a pump-action shotgun.

Here comes her husband now, stepping into an Italian restaurant: Shaved head, goatee, shades, jeans, embroidered white silk shirt (untucked), flip-flops, baseball cap, biceps, blue eyes, 47. About 6-1, 220, former honorable-mention all-Pac-10 wide receiver at the University of Arizona. He is "fully sleeved," as they say in the world of skin ink, tattoos covering both arms, shoulder to wrist. Silver rings on almost every finger. Espresso addict, chain smoker. He's stopped doing handfuls of Hydroxycut, the diet pills, the legal uppers, that kept him stoked when he was riding with the Angels, hands thrown up on the ape hangers, but he still looks like if he hit you, you'd stay hit.

"I'm not anybody's knight in shining armor," he's saying, explaining why he's committing career suicide, filing suits like this, alerting members of Congress of his claims, "but there's a greater good here. Nobody has ever stood up to these guys before."

He digs into the pasta and flips through the shorthand notes he penned in all capital letters, in red ink, for today's interview: "Only people who hate me more than the Hells Angels are ATF's shot-callers." And: "I have God and a gun on my side -- I will be OK." And: "U.S. gov't left me alone to defend my family from an international crime syndicate."

He's no longer in hiding; he's full-bore into the lawsuits. He'll go on for two minutes or two hours, it's up to you, about how the ATF accused him of burning his own house down and said he was "mentally unfit" to work. He says a recent mediation hearing produced this offer from the agency: Quit or be fired.

One suit was filed last October in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims in D.C.; the ATF is contesting the venue. The other suit, filed in federal court in Arizona in March, is not yet due for a response from the agency. A spokesman declined to comment on Dobyns's allegations. More on that in a minute.

First, let's go back to the beginning. The Hells Angels case was supposed to be a career capper.

Dobyns, an undercover agent with ATF for 15 years, was a highly regarded pro working a case in Bullhead City, Ariz., in 2001, with the covert identity of Jay "Bird" Davis. He was posing as a gun-runner and collections-agent thug for the fictional business Imperial Financial.

He was in mid-investigation in April 2002 when the Angels and the Mongols, another rough-hewn cycle gang, fell into a riot at Harrah's casino in Laughlin, Nev. Two Angels and one Mongol were killed and dozens injured. The ATF decided to go after the 2,500-member Angels, with the theory that the gang constituted a racketeering organization.

To do this, Dobyns and another agent put together a "gang," composed of two other undercover agents and two paid informants. The lead informant, Rudy Kramer, was a longtime biker and meth dealer, and an inactive member of a Tijuana-based cycle gang called the Solo Angeles. Their gang had Kramer as president, Dobyns as vice president. They would tool around Arizona, profess their love and admiration for the Hells Angels and ask for permission to set up a formal nomad chapter of the Solo Angeles in their area. From there, they'd try to worm their way into the Angels' good graces and alleged criminal doings, thereby laying the groundwork for a massive conspiracy indictment.

Dobyns's group worked for nearly two years. They rode thousands of miles with the Angels. He learned things; he could wave off drinks by always having a smoke in hand. "I sacrificed my lungs to save my liver." He could pass on hits of cocaine, weed and meth by saying that he worked for a Mafia boss who kept him on call every hour of every day. He enlisted a female agent to pose as his girlfriend, to give him a plausible excuse to pass on the offers of sex from female hangers-on.

He went so deeply into being Bird that he says he became "obsessed," all but forgetting his wife and children. It took a toll on his marriage. He got a lot of tattoos, mainly from an Angel named Robert "Mac" McKay, and hammered down caffeine, Red Bulls and diet pills to get that eyes-glazed gonzo look.

He and a colleague staged an execution of a Mongol (actually, another cop) to impress the Angels brass. They dressed the cop in Mongols gear, tied his hands behind his back, put him face down in the desert, then mussed cow brains through his hair and spattered his clothes with blood. They took a happy snap of the gore and brought back the bloody Mongol vest. That earned Dobyns an invitation to join the club, and then the net swooped in for the arrests.

"I felt like Lewis and Clark when they laid eyes on the Pacific, or Neil Armstrong when his boot hit moon dirt," he writes in the book.

Not afraid of publicity, he went on cable television documentaries, even wearing a cowboy hat in one, describing his exploits. Two true-crime books were written about the investigation before his own memoir. He set up a slick Web site, showcasing his college football heroics, his bad-ass biker persona (scowl, bandanna, tats, bulging biceps, the obligatory wife-beater) and his motivational speaking gigs.

This is all great . . . except for the unhappy fact that the case collapsed before trial. No Angel did time for anything much more serious than being in possession of a firearm. Most of them walked. Dobyns says it was due to infighting between ATF higher-ups and the local prosecutor's office.

Then came the threats. He and his family went on the run, his suit maintains, and the ATF mishandled the moves, delayed investigating the threats and came to regard him as a showboating pain in the rear.

"In nearly every respect, [the Angels] won," he writes in the book. Let's talk to some Hells Angels. Let's see what they make of Jay Dobyns. Let's start at the top, the godfather of the band, Sonny Barger.

We've got his attorney Fritz Clapp on the line, and we're explaining about Dobyns and death threats and we'd like to see what Mr. Barg -- "We're not giving him any publicity to sell his book," Clapp interrupts, amicably. "No comment."

Fine. We ask for his official title with the Angels, and Clapp says, "I'm the guy who says, 'No comment.' " He went on to trade bike stories, about this time he was injured and several bikers were killed in a collision with a runaway pulpwood truck -- "It was raining logs" -- but we digress.

Let's talk to an Angel who allegedly threatened to kill Dobyns.

"The man's a sociopath." This is Robert "Mac" McKay on the line -- an Angel calling a cop a sociopath, what are the odds -- from his tattoo shop, the Black Rose, in Tucson. McKay spent 17 months in jail awaiting trial on a variety of charges after Dobyns's investigation. He eventually took a plea to a single misdemeanor for threatening Dobyns in a bar.

"The whole investigation thing, the government spent millions of dollars on what turned out to be a publicity stunt for Jay Dobyns," McKay says. He adds that the alleged threat was "a total fabrication."

So, do the Angels want Dobyns dead? Did they cause his house to burn down?

"Absolutely not. He is not under any threat from us and never has been. He's got this thing in his mind about who he is. . . . Even the ATF says he's useless."

McKay's court-appointed lawyer, Barbara Hull, says, "The whole case went south quickly, and it was pretty clear it had to do with Agent Dobyns."

The assistant U.S. attorney who prosecuted the case, Tim Duax, now based in Iowa, says that's nonsense.

"Jay's undercover work was solid," Duax says. The allegation that he did something unethical that deep-sixed the case? "Absolutely untrue." The reason the case disintegrated? "Had nothing to do with Agent Dobyns."

So how did it come to this, sitting in a restaurant, giving a postmortem on his career? Dobyns says it's simple: The threats came in, were mishandled, he complained in high-octane fashion and alienated people high up in the organization. His suit is filled with allegations that superiors have told him he'll be ending his career in "a postage stamp in the middle of nowhere," that they think he burned down his own house.

"They took three days to send anybody out to look at the house," he says. "And when I complained about their offered solution -- to move us again -- within two hours they told me I was the chief suspect."

This does not strike some veteran agents as unusual. William "Billy" Queen is a legendary ATF agent who infiltrated the Mongols in California several years ago, netting dozens of felony convictions for serious crimes. His reward, he says, was that "the ATF ruined my life."

He says that when the agency moved him out of the area to protect him from death threats, he was needlessly split from his ex-wife and children (who lived nearby, and wanted to relocate with him). They were shipped to Miami. He was shipped to Plano, Tex. He cites a personal vendetta from a high-ranking (now retired) ATF administrator as the cause. It was so bad, Queen says, that he retired.

"What they did to me was worse than what they've done to Jay," he says, in a telephone interview from his home in California. He never sued but "looking back on it now, I wish I would have."

Charlie Fuller, the executive director of the International Association of Undercover Officers, spent 23 years with the ATF. He trained undercover agents for the agency for years, including Dobyns. He says that while he loves his former employer, it has an "institutional suspicion" of its undercover agents.

"ATF considers undercovers a necessary evil," Fuller says. "They don't fit the mold. They don't look like the chief of police. Jay didn't do dope, didn't cheat, didn't beat people up. That's actually hard to do, in those operations, with those type of people, but ATF can't believe that. They can't believe you work guys like that and not do all that stuff. That's what they visualize."

Still, he says, when he heard the agency was saying that Dobyns set fire to his own house, "it sent me over the edge. I can't tell you how this is eating at me."

The ATF was asked about these and other statements. Here is the response:

"ATF is aware of the recent publication of Mr. Dobyns' book. The book is not an ATF publication, and as such, ATF will not comment on its content. Further, ATF does not, as a matter of policy, comment on personnel matters or pending litigation." It's attributed to W. Larry Ford, the assistant director for public and governmental affairs.

Jay Dobyns finishes his lunch and heads back out into the sunshine. He's got another meeting, something to do with the lawsuit, before catching a flight back home. Shades and baseball cap back on. He's hurrying. He's got a sense of purpose. He's not happy. Blue-eyed crime fighters with prominent jaws aren't supposed to end up like this.

Watching him go, you wonder how it's all going to end, the jilted agent now fighting his own agency, and it doesn't look good for anybody. Maybe he was right. Maybe the Angels, still riding, still the most powerful motorcycle gang on the planet, really did run over him.

Former All-American Supercop Jay Dobyns, the federal agent who went undercover to infiltrate the Hells Angels, leaves his Georgetown hotel on a recent hot afternoon. Shoves his pistol into his waistband at the small of his back, lights a Marlboro and crosses M Street NW.

"I'm the good guy," he says, as if reminding you to keep your eye on the ball.

He's still employed by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in an Arizona office job, but it's clear the agency has had enough of his Serpico bit, the whole Donnie Brasco thing. Dobyns is the best-selling author of this year's "No Angel," a taut, profane tome about how he worked his way into the Arizona chapter of the world's most notorious motorcycle gang, and sure, the movie rights have already sold.

But more important, he's filed two suits against the ATF, charging the agency with failing to protect him from years of death threats from bad men on big bikes.

The U.S. Department of Justice's Office of the Inspector General issued a report last year that said he was right -- that the agency had failed to move him and his family with their identities protected, that the ATF's response to one death threat was "inadequate, incomplete and needlessly delayed," that they had reached dismissive conclusions about the threats "without adequate investigation," and so on. The report recommended the ATF "amend its written procedures" to better protect all agents.

He's moved his family more than 10 times in four years, sometimes at government expense, sometimes at his own. He's changed his names on official records. And still, an unknown arsonist found and torched his Tucson house one night last August, while he was traveling, sending his wife and two teenage children sprinting into the darkness. An Angel in prison was caught writing a letter to another gang member, saying they should arrange for the gang rape of Dobyns's wife, Gweneth.

"Doesn't sound like a fun evening, does it?" she says, by phone. They've been married 20 years. She sounds great, like Sondra Locke in those Clint Eastwood flicks from the 1970s, a nice girl with good hair who's handy with a pump-action shotgun.

Here comes her husband now, stepping into an Italian restaurant: Shaved head, goatee, shades, jeans, embroidered white silk shirt (untucked), flip-flops, baseball cap, biceps, blue eyes, 47. About 6-1, 220, former honorable-mention all-Pac-10 wide receiver at the University of Arizona. He is "fully sleeved," as they say in the world of skin ink, tattoos covering both arms, shoulder to wrist. Silver rings on almost every finger. Espresso addict, chain smoker. He's stopped doing handfuls of Hydroxycut, the diet pills, the legal uppers, that kept him stoked when he was riding with the Angels, hands thrown up on the ape hangers, but he still looks like if he hit you, you'd stay hit.

"I'm not anybody's knight in shining armor," he's saying, explaining why he's committing career suicide, filing suits like this, alerting members of Congress of his claims, "but there's a greater good here. Nobody has ever stood up to these guys before."

He digs into the pasta and flips through the shorthand notes he penned in all capital letters, in red ink, for today's interview: "Only people who hate me more than the Hells Angels are ATF's shot-callers." And: "I have God and a gun on my side -- I will be OK." And: "U.S. gov't left me alone to defend my family from an international crime syndicate."

He's no longer in hiding; he's full-bore into the lawsuits. He'll go on for two minutes or two hours, it's up to you, about how the ATF accused him of burning his own house down and said he was "mentally unfit" to work. He says a recent mediation hearing produced this offer from the agency: Quit or be fired.

One suit was filed last October in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims in D.C.; the ATF is contesting the venue. The other suit, filed in federal court in Arizona in March, is not yet due for a response from the agency. A spokesman declined to comment on Dobyns's allegations. More on that in a minute.

First, let's go back to the beginning. The Hells Angels case was supposed to be a career capper.

Dobyns, an undercover agent with ATF for 15 years, was a highly regarded pro working a case in Bullhead City, Ariz., in 2001, with the covert identity of Jay "Bird" Davis. He was posing as a gun-runner and collections-agent thug for the fictional business Imperial Financial.

He was in mid-investigation in April 2002 when the Angels and the Mongols, another rough-hewn cycle gang, fell into a riot at Harrah's casino in Laughlin, Nev. Two Angels and one Mongol were killed and dozens injured. The ATF decided to go after the 2,500-member Angels, with the theory that the gang constituted a racketeering organization.

To do this, Dobyns and another agent put together a "gang," composed of two other undercover agents and two paid informants. The lead informant, Rudy Kramer, was a longtime biker and meth dealer, and an inactive member of a Tijuana-based cycle gang called the Solo Angeles. Their gang had Kramer as president, Dobyns as vice president. They would tool around Arizona, profess their love and admiration for the Hells Angels and ask for permission to set up a formal nomad chapter of the Solo Angeles in their area. From there, they'd try to worm their way into the Angels' good graces and alleged criminal doings, thereby laying the groundwork for a massive conspiracy indictment.

Dobyns's group worked for nearly two years. They rode thousands of miles with the Angels. He learned things; he could wave off drinks by always having a smoke in hand. "I sacrificed my lungs to save my liver." He could pass on hits of cocaine, weed and meth by saying that he worked for a Mafia boss who kept him on call every hour of every day. He enlisted a female agent to pose as his girlfriend, to give him a plausible excuse to pass on the offers of sex from female hangers-on.

He went so deeply into being Bird that he says he became "obsessed," all but forgetting his wife and children. It took a toll on his marriage. He got a lot of tattoos, mainly from an Angel named Robert "Mac" McKay, and hammered down caffeine, Red Bulls and diet pills to get that eyes-glazed gonzo look.

He and a colleague staged an execution of a Mongol (actually, another cop) to impress the Angels brass. They dressed the cop in Mongols gear, tied his hands behind his back, put him face down in the desert, then mussed cow brains through his hair and spattered his clothes with blood. They took a happy snap of the gore and brought back the bloody Mongol vest. That earned Dobyns an invitation to join the club, and then the net swooped in for the arrests.

"I felt like Lewis and Clark when they laid eyes on the Pacific, or Neil Armstrong when his boot hit moon dirt," he writes in the book.

Not afraid of publicity, he went on cable television documentaries, even wearing a cowboy hat in one, describing his exploits. Two true-crime books were written about the investigation before his own memoir. He set up a slick Web site, showcasing his college football heroics, his bad-ass biker persona (scowl, bandanna, tats, bulging biceps, the obligatory wife-beater) and his motivational speaking gigs.

This is all great . . . except for the unhappy fact that the case collapsed before trial. No Angel did time for anything much more serious than being in possession of a firearm. Most of them walked. Dobyns says it was due to infighting between ATF higher-ups and the local prosecutor's office.

Then came the threats. He and his family went on the run, his suit maintains, and the ATF mishandled the moves, delayed investigating the threats and came to regard him as a showboating pain in the rear.

"In nearly every respect, [the Angels] won," he writes in the book. Let's talk to some Hells Angels. Let's see what they make of Jay Dobyns. Let's start at the top, the godfather of the band, Sonny Barger.

We've got his attorney Fritz Clapp on the line, and we're explaining about Dobyns and death threats and we'd like to see what Mr. Barg -- "We're not giving him any publicity to sell his book," Clapp interrupts, amicably. "No comment."

Fine. We ask for his official title with the Angels, and Clapp says, "I'm the guy who says, 'No comment.' " He went on to trade bike stories, about this time he was injured and several bikers were killed in a collision with a runaway pulpwood truck -- "It was raining logs" -- but we digress.

Let's talk to an Angel who allegedly threatened to kill Dobyns.

"The man's a sociopath." This is Robert "Mac" McKay on the line -- an Angel calling a cop a sociopath, what are the odds -- from his tattoo shop, the Black Rose, in Tucson. McKay spent 17 months in jail awaiting trial on a variety of charges after Dobyns's investigation. He eventually took a plea to a single misdemeanor for threatening Dobyns in a bar.

"The whole investigation thing, the government spent millions of dollars on what turned out to be a publicity stunt for Jay Dobyns," McKay says. He adds that the alleged threat was "a total fabrication."

So, do the Angels want Dobyns dead? Did they cause his house to burn down?

"Absolutely not. He is not under any threat from us and never has been. He's got this thing in his mind about who he is. . . . Even the ATF says he's useless."

McKay's court-appointed lawyer, Barbara Hull, says, "The whole case went south quickly, and it was pretty clear it had to do with Agent Dobyns."

The assistant U.S. attorney who prosecuted the case, Tim Duax, now based in Iowa, says that's nonsense.

"Jay's undercover work was solid," Duax says. The allegation that he did something unethical that deep-sixed the case? "Absolutely untrue." The reason the case disintegrated? "Had nothing to do with Agent Dobyns."

So how did it come to this, sitting in a restaurant, giving a postmortem on his career? Dobyns says it's simple: The threats came in, were mishandled, he complained in high-octane fashion and alienated people high up in the organization. His suit is filled with allegations that superiors have told him he'll be ending his career in "a postage stamp in the middle of nowhere," that they think he burned down his own house.

"They took three days to send anybody out to look at the house," he says. "And when I complained about their offered solution -- to move us again -- within two hours they told me I was the chief suspect."

This does not strike some veteran agents as unusual. William "Billy" Queen is a legendary ATF agent who infiltrated the Mongols in California several years ago, netting dozens of felony convictions for serious crimes. His reward, he says, was that "the ATF ruined my life."

He says that when the agency moved him out of the area to protect him from death threats, he was needlessly split from his ex-wife and children (who lived nearby, and wanted to relocate with him). They were shipped to Miami. He was shipped to Plano, Tex. He cites a personal vendetta from a high-ranking (now retired) ATF administrator as the cause. It was so bad, Queen says, that he retired.

"What they did to me was worse than what they've done to Jay," he says, in a telephone interview from his home in California. He never sued but "looking back on it now, I wish I would have."

Charlie Fuller, the executive director of the International Association of Undercover Officers, spent 23 years with the ATF. He trained undercover agents for the agency for years, including Dobyns. He says that while he loves his former employer, it has an "institutional suspicion" of its undercover agents.

"ATF considers undercovers a necessary evil," Fuller says. "They don't fit the mold. They don't look like the chief of police. Jay didn't do dope, didn't cheat, didn't beat people up. That's actually hard to do, in those operations, with those type of people, but ATF can't believe that. They can't believe you work guys like that and not do all that stuff. That's what they visualize."

Still, he says, when he heard the agency was saying that Dobyns set fire to his own house, "it sent me over the edge. I can't tell you how this is eating at me."

The ATF was asked about these and other statements. Here is the response:

"ATF is aware of the recent publication of Mr. Dobyns' book. The book is not an ATF publication, and as such, ATF will not comment on its content. Further, ATF does not, as a matter of policy, comment on personnel matters or pending litigation." It's attributed to W. Larry Ford, the assistant director for public and governmental affairs.

Jay Dobyns finishes his lunch and heads back out into the sunshine. He's got another meeting, something to do with the lawsuit, before catching a flight back home. Shades and baseball cap back on. He's hurrying. He's got a sense of purpose. He's not happy. Blue-eyed crime fighters with prominent jaws aren't supposed to end up like this.

Watching him go, you wonder how it's all going to end, the jilted agent now fighting his own agency, and it doesn't look good for anybody. Maybe he was right. Maybe the Angels, still riding, still the most powerful motorcycle gang on the planet, really did run over him.